I wasn’t ready. I would never be ready. Still, I took a deep breath. I loaded the video, and I hit play.

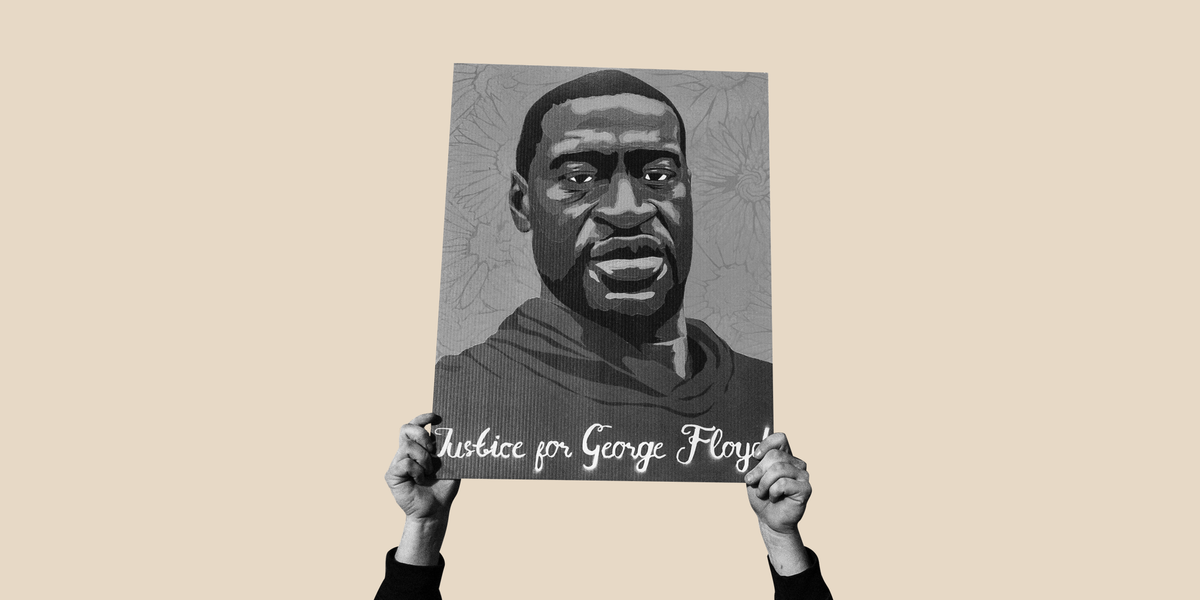

How long did I watch? Not the full 9 minutes and 29 seconds, but long enough to know George Floyd would not survive.

Tears came easily for me during that time, and not just because the world was in the early days of a pandemic that had no clear indication of ending anytime soon. Just weeks before seeing what happened to George Floyd, I’d read what had happened to Breonna Taylor in Kentucky. I’d read what had happened to Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia. And in between all of that, I’d learned that my grandfather had passed away in Illinois after a years-long battle with dementia and Parkinson’s disease. COVID-19 kept me from the funeral.

The 600-square-foot studio apartment in which my partner and I had been quarantining couldn’t hold all of that grief. Neither could I. So, the next day, when a friend texted about an upcoming protest in Brooklyn, my partner and I talked over the pros and cons of joining her. Attending would mean pushing back my upcoming family visit to Connecticut, and it would also mean risking exposure to the coronavirus. Police officers might come to the protests prepared for a fight, and that could mean…well, we’d seen what that could mean.

Still, we put on our masks, stuffed our pockets with hand sanitizer, and went out into the world.

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

This was a new experience. See, protest is in my blood. But for most of my young life, protest was not for me.

In 2014, the evening that a grand jury decided not to indict the cop who killed Eric Garner, I watched the protests from my computer, a bowl of Rice-A-Roni in my hands. My dad called to ask where I was; he assumed I was out on the streets. I told him I was home. I’d had a long day of work and grad school classes. Besides, I didn’t even have anybody to protest with. I’d been fairly new to the city and hadn’t made many friends yet.

My dad listened. He understood my excuses. “There are different ways to protest,” he said, acknowledging that my writing was one of them. Yet I couldn’t ignore the guilt I felt getting my news from CNN rather than my own eyes, because I couldn’t shake the one excuse I’d neglected to admit: I was scared.

Historically, the Harrises don’t get scared. My dad was one of the first Black children to integrate his elementary school in Waukegan, Illinois, in the late ’60s. As a teenager, a police officer stopped him for no other reason than Walking While Black. He’s been called the N-word as a child and as an adult. In the early ’90s, his employer discriminated against him so blatantly that he filed a lawsuit against them.

The discrimination I’ve experienced has been far less pronounced. I grew up in mostly white spaces; I wasn’t all that conscious of my otherness, and my white friends didn’t seem to be either. It wasn’t until I reached my early 20s—until I really started to see how frequently Black lives were being taken without any repercussions—that I fully understood what my Black skin meant to other people and, more importantly, what it meant to me. It meant knowing that no matter how quickly or politely I complied, a police officer could still see my brown skin and make a catastrophic decision because of it. It meant knowing that my existence would be challenged or questioned for the rest of my life, and that it would be on me to prove why it mattered. I understood why my dad risked our family’s financial security suing his employer in order to stand up for what was right. And I understood why my late grandfather, once a leader of his local NAACP chapter, risked everything to fight segregation in Waukegan schools.

This was why, in 2020, as my partner and I marched with hundreds of other protesters, shouting and sanitizing and clapping and giving each other as much space as we could, I knew I was doing the right thing.

And this was why I felt so bummed—and so shocked—to hear that my dad didn’t support my decision to protest. He felt it was unsafe.

“We were careful though,” I said, sounding more like I was 17 than 27. “Everybody was careful.”

But Dad wouldn’t hear it. He was adamant. Upset even. He spoke of the dangers of the virus, of how he wanted me to be around to see my novel, The Other Black Girl, come out in 2021. He wanted me to be around—period. Because the virus, much like the police, had been especially cruel to Black people. My dad wanted to protect his children, especially as so many Black lives were being stolen and especially in the wake of losing his own father.

I listened. I understood. But I also didn’t. Speaking up was a Harris Thing! I expected him to be proud; I expected him to see himself in my decisions. Didn’t he remember the letter his own father had written him 30 years earlier, when he was doubting the lawsuit against his employer? My grandfather wrote, “History is on the side of the risk takers—the ones who threw down the gauntlet and made personal commitments.”

In the months after my grandfather’s passing, I revisited this letter frequently, grateful I had thought to save a copy in my Google Drive the previous year. The way I saw it, I wasn’t risking what Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman had risked when they set out to register Black Mississippians to vote, nor what my grandparents and countless other activists had risked when they marched for equality during the Civil Rights Movement. I could afford to protest. I didn’t have a 9-to-5 job or children or preexisting health conditions.

And I desperately wanted not to feel so helpless. Protesting meant having my voice be heard, but it also meant having the space to let out my frustration, my grief. My forthcoming novel about four Black women struggling to succeed in white corporate America was its own form of protest, sure. But writing wasn’t enough for me. My grief and I preferred to be out in the world screaming “Black lives matter” with hundreds of other people who also felt the risk wasn’t just worth it but absolutely necessary.

A few weeks later, my phone rang. It was my dad’s mom. “Your dad told me you’ve been out protesting,” Grandma started. Great, I thought, bracing myself. He’s enlisted reinforcements.

But a lecture didn’t come. What came instead was much, much sweeter. “I just called to tell you that I am so proud of you, Zakiya. And I know your grandfather is looking down on you, and he’s proud too,” she said.

My grandparents worked to give my parents more than they had, and my parents did the same for my sisters and me. But there is always more work to be done, and there is only so much one person can do. Perhaps each of us need to carry the weight for a little while—throw down the gauntlet however we choose—so that one day, we each have a chance to rest.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io